It’s Friday July 5th, the sun is shining, it’s a beautiful day. I called up Monica and asked her if she wanted to go out for dinner. We set a date to meet at Celebracion Café at 5:00pm. Upon arrival we search for appropriate parking, to discover that the person parked next to us has encroached over the line. Therefore, there is not enough space for us to lower the ramp so I can exit the vehicle. Finally, after what seemed forever, waiting for them to move their car. I realized that the ramp for the plaza sidewalk was halfway across the parking lot and was extremely narrow. With so assistance we finally navigate the walkway to make it to the front door, only to find no automatic door and a double door entry. This makes it very difficult as Monica cannot hold both doors open at the same time. To make matters worse, people are walking right past us, thinking she is holding the door for them. Phew, we are finally inside after 20 minutes of battling over the inaccessibility of the plaza and restaurant. Monica and I make our way towards the hostess desk, making sure not to run over anyone’s feet, as the space is quite small.

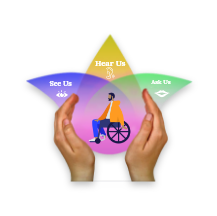

Accessibility is Critical

Exposure is Essential

Accessibility

Once we get the attention of the hostess, we asked for a table for two with wheelchair accessibility. We are directed towards our table, as the stares and glares of other customers come our way. Instead of receiving two menus, the hostess only gives one to Monica, we ask for a second one, only to get an eye roll from her. It has been a while since Monica, and I have had a chance to get out together and enjoy catching up. The hostess arrives back at our table with a child’s menu and crayons. Our server comes to take our order and directs all her questions towards Monica and acts as if I’m not even there, what can I get you and her to drink, are you ready to order? I immediately start speaking, and the server turns a tomato shade of red. After I finish placing my order, the server looks back at Monica and says, “okay I will bring you and her your drinks.” Our drinks and food arrive; however, we notice only one set of cutlery on the table and have to ask for a second set. While we are waiting for the cutlery, Monica goes into our prepared bag and gets my special cup (because the restaurant cups are too heavy) and my tea cloth (to cover my shirt). Once we have the cutlery needed, Monica assists me in cutting up my food and placing the plate on my right-hand side and filling my cup up with the drink I have ordered. When our server returns to check in, she still directs her questions to Monica as if I not there. We finish up our meal, ask to the bill and venture back out into the accessibility nightmare. Even though Monica and I enjoyed our time together, it is very hard to fully appreciate our time catching up, due to all the obstacles and stereotypical assumptions made towards me.

Monica and I are best friends. She has her PhD in social work. I met her while I was completing my BSW (Bachelor of Social Work). Together we have worked on building communities for students with mental health issues and/or other (dis)Abilities. We are not strangers to the world of stupidity, being silenced or being forced into taking center stage, but with a little humour and help from each other, we get by. We have ditched the metaphorical business suits and fancy ties along with that all knowing attitude, we refer to those people as ‘shiny people’. Pretty things deserve to be shiny and the situations we find ourselves in leave much to be desired, but one day we will write a book. Our dining experience would be one of the many chapters. We are both irritated but unfazed, I guess if you wear your suit too tight it can cut off valuable oxygen to the brain. When Monica and I decide to get together, we are free from our daily routines of preparation and worry. We are just two friends going out for dinner. Monica and I recognize that this goes far beyond stupidity, rather this situation is layered and can create structural, cultural, and interpersonal level oppression. However, this is our way of removing ourselves from an ableist culture that we are inextricably a part of. There may be similar cases with ableism, that my research participants encounter and hopefully will be able to share how they deal with those situations.

The purpose of this story is to show how hyper-visibility/invisibility ties into ableist constructs. I recognize that the built environment is essential in terms of physical access. However, we must acknowledge that the access may be available, but it is often not collaborated with wheelchair users. Therefore, in some cases full and unhindered access is not truly attainable.

Restaurant managers and owners may be hesitant to increase accessibility in their facilities due to increased cost and less revenue (Rosetti, 2009). For example, if seating was spread further apart for wheelchair access it would allow for less seating for able-bodied customer use (Rosetti, 2009). It is important to remember the differences between universal design and accessibility (Spence, 2018). Accessibility proposes solutions for the (dis)Ability community and universal design is focused on the usability of the environment for all person, regardless of their ability (Spence, 2018). Universal design creates solutions that work on a continuum as you are trying to design to be as inclusive as possible (Spence, 2018). If you imagine universal design on a continuum, you still may not account for everyone’s needs, however, there is less of a chance of not attaining the desired outcome, if you do your best to consider the needs of everyone (Spence, 2018). Finding the right design fit that incorporates the various accessibility needs of different groups may be challenging (Spence, 2018). By using universal design access ‘always-already’ exists in everyday structures without drawing attention to the accessibility requirement (Suetzl, 2022).

In phenomenology the term ‘always-already’ refers to things that have been always-already there. When thinking about the built environment, they are structures that have been incorporated within the design and not something that is added, due to special needs of a specific group (Suetzl, 2022). For example, having lower sinks and mirrors in restaurant bathrooms benefit wheelchair users, however, it can also benefit young children, little people, seniors with walkers or anyone else who is short in stature (Suetzl, 2022). Rate-It is an instrument used to evaluate the functional accessibility of restaurants that includes dining areas, restrooms, education for restaurant staff, entrance ways and indoor pathways (Park, Park, Park & Smith, 2020). Using this assessment tool in the planning process can help reduce feelings of ableism, hyper-visibility, and invisibility. This may help to give persons with (dis)Abilities more equitable access to restaurants and be able use the restaurant setting as a platform to engage in social relations with others, thus reducing social isolation (Park et al, 2020). When it comes to universal design, our actions are more important than what we say we believe, (dis)Abled bodies may be subject to exclusion within the built environment (Slayter, Kattari, Yakas, Singh, Goulden, Taylor, Wernick, Simmons & Prince, 2022). However, through education and self-awareness we can help society suspend natural attitudes and using are inherent able-bodied privilege (the ability to move freely within society without mobility/accessibility issues) to help create change.

Education goes far beyond understanding accessibility needs, it may also include such areas as inclusion, inter-personal interactions and the visibility of the lives and desires of PWD. This was clearly demonstrated in the video above where a woman in a wheelchair is refused access into a restaurant due to her ‘inappropriate’ footwear, the manager informs her that she must be in high heels. Within today’s culture, beauty ideals are closely tied to affordances that allow recognition within society, as these normative bodies gain visibility and tend to be celebrated rather than stereotyped (Foster & Pettinicchio, 2021). As research shows, some people in wheelchairs may be told ‘you are too pretty to be in a wheelchair’ (Foster & Pettinicchio, 2021). However, as the video plays on, we can clearly see that even when the woman in the wheelchair buys appropriate footwear, her interactions are still entrenched in invisibility, hyper-visibility, and ableism. A system of social closure and domination happens for some people with (dis)Abilities, as some are seen, but not all (Hoppe, 2021). For example, in the video when the woman in the wheelchair is refused washroom access, stating that they are not made for people like her. Having access to washrooms is a human right and often lack of access to washrooms is not even questioned, because it is considered common place ‘sensible’ (Titchkosky, 2008). In phenomenology our perception and language are a gesture that carries meaning within worldly interactions (Merleau-Ponty, 2013). The language we choose to use to justify truth claims around inaccessible washrooms may help to justify why they may not be available (Titchkosky, 2008). For example, saying that washrooms were not built for people like you, may give the restaurant a sense that their logic operates on sheer sensibility, regardless of if the perception is seen as good or bad, natural stereotypical attitude then becomes unquestioned and ingrained.

As one can see life of PWD is complex, it is important to include PWD in the design and delivery aspect of pre-existing and new builds when considering accessibility needs. This may help with improving attitudes on a structural, systemic, and inter-personal levels, as all human-beings deserve to be treated with dignity and inclusion regardless of their appearance.